Unlocking Venezuela’s oil rebirth

Summary

The 2026 Hydrocarbons Law Reform represents the greatest liberalisation of Venezuela’s oil sector since its nationalisation in 1976.

The Reform is being complemented by other political changes and a progressive easing of U.S. sanctions on the industry.

In a conservative scenario, crude oil production could rise to 1.3 Mbpd by the end of 2026, and 1.7 Mbpd by the end of 2027.

Orinoco Oil Belt wellhead costs are comparable to those in the Alberta Oil Sands and well below those in major U.S. geological formations, offering attractive investment opportunities.

1. A bird’s eye view of Venezuelan oil

Venezuela’s natural resource wealth is once again under the spotlight on the world stage. After the U.S. military intervention on January 3, the country is undergoing political and economic reforms, while President Donald Trump has called on Big Oil to invest there. In the meantime, his administration is gradually easing sanctions through general licenses.

Some have challenged the claim that Venezuela has the world’s largest oil reserves: the 300 billion barrels figure refers to proven, recoverable reserves, while other countries may have larger, uncertified deposits. The nation is still ranking at the top, but its production and exports are negligible globally. And some energy executives are not heeding President Trump’s call, raising concerns with the viability of investing in an unstable country without a clear framework.

The industry faces many questions. What needs to happen to revive Venezuela’s oil sector? How fast can production recover? Can the country ever rival the world’s giants again? And, finally, is it worth it? Is Venezuelan oil uninvestable? These questions are not just vital to energy firms, but also to all investors with exposure to Venezuela: its future hinges on black gold.

The South American country’s oil sector is undoubtedly overwhelmed by many challenges. Many inefficiencies and a run-down infrastructure rock the industry. U.S. sanctions, along with high levels of risk and uncertainty, have kept investment away. Despite all this, some companies have recovered production in certain oil fields and quickly turned a profit. Some industry insiders are already saying that Venezuela “could be the biggest commodities opportunity after the fall of the Soviet Union.”

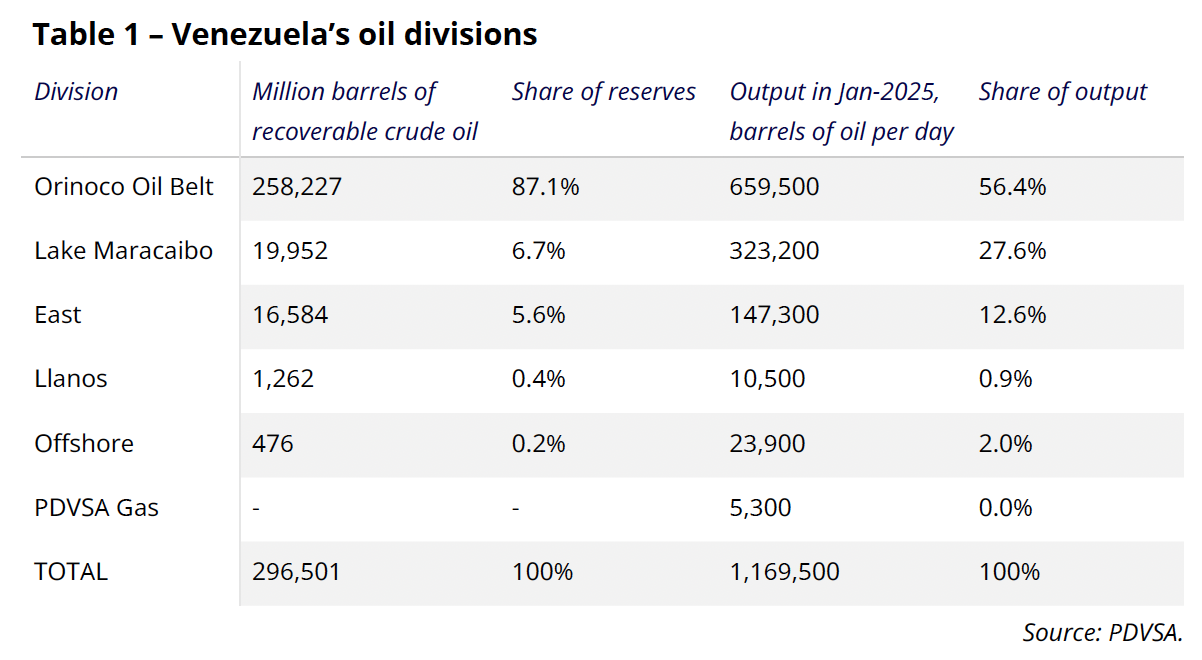

Broadly, we can divide Venezuela’s oil sector into six divisions, with three being the most significant: the Orinoco Oil Belt (Faja Petrolífera del Orinoco in Spanish), Lake Maracaibo, and the East (Oriente in Spanish).

Orinoco Oil Belt (Faja Petrolífera del Orinoco): Running along the northern shores of the Orinoco River, this formation contains one of the largest single deposits of hydrocarbons, comparable to the Alberta Oil Sands. The key challenge, however, is to efficiently extract its extra-heavy crude grades, which require diluents and more advanced technologies and infrastructure. This region also includes many greenfield areas. The same Belt flares and vents close to 2 billion cubic feet per day of associated gas, which could become an additional source of energy and revenues with the right sector reforms. Future infrastructure investments could connect the Belt to Trinidad’s existing facilities for liquefying and exporting natural gas.

Lake Maracaibo: Venezuela’s oil industry first developed here, and the region’s infrastructure is thus more developed. With 6.7% of the reserves, it produces 26.5% of the barrels. This division combines shallow offshore fields and onshore fields along the lake’s banks, with a mix of light, medium, and heavy crudes. It feeds the Paraguaná Refinery Complex, with an installed capacity of 955,000 bpd—second only to India’s Jamnagar Refinery. Another advantage is that it borders Colombia, and a gas pipeline already exists; it only needs some repairs. In the near future, associated gas from this division, alongside that from the Perla gas field, could be used to meet the neighbouring country’s energy deficit.

East (Oriente): With fewer reserves, it has the advantage of being situated between the Orinoco Oil Belt and the José Antonio Anzoátegui oil terminal and petrochemical complex. It also hosts much of the infrastructure needed to process heavy oil, including upgraders. In the past, fields in this region have supplied PDVSA with light and medium crude oil needed to complement the Belt.

2. The Hydrocarbons Law Reform of 2026: Unprecedented liberalisation

The Hydrocarbons Law Reform of 2026 represents the most extensive concession to private investment ever made in Venezuela since the nationalisation of the industry in 1976, even when we consider the period of opening up in the 1990s.

First, the Reform sets in stone various pragmatic changes introduced in recent years, such as the so-called “Chevron model” and various production-sharing agreements. They contradicted the original legislation for the industry, while they were protected by the Anti-Blockade Law of 2020.

These changes essentially investors a lower government take and operational control. Oil companies investing in Venezuela can now manage finances, sell oil directly, and purchase goods and services without involving state-owned PDVSA.

Then, the Reform introduces a reduction of royalties and taxes across the board. However, there is an important element of arbitrariness for the Executive, which currently is represented by the Ministry of Hydrocarbons. It has the power to negotiate how low the government take will be with each investor, based on a set of vague criteria. The National Assembly or other powers no longer have any say.

The Reform also stipulates that disputes must be resolved through international courts and mediation, rather than exclusively inside Venezuela. The first Trump general licenses ask that contracts be governed by U.S. law, meaning that the two measures could be intended to be complementary.

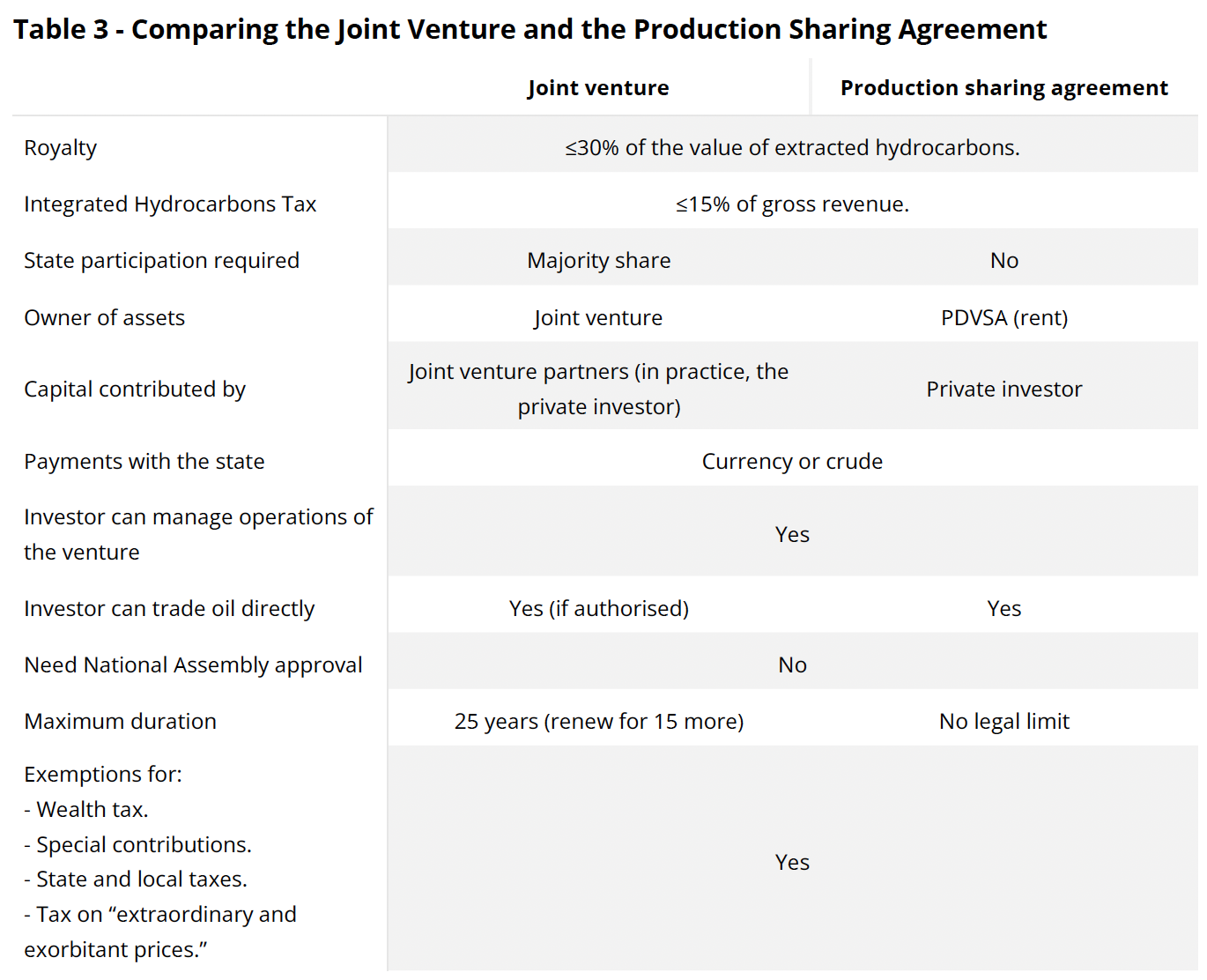

Currently, there are two types of agreement to produce oil in Venezuela. With the latest changes, the two frameworks have converged and present many of the same conditions.

Joint Venture: The standard system for the last two decades, where PDVSA is required to have a majority stake. Used by most energy majors, including Chevron, CNPC, and Repsol currently, and others like TotalEnergies, ExxonMobil, and BP in the past.

Production Sharing Agreement: The current form is the Contrato de Participación Productiva or CPP, which is being employed by comparatively smaller firms, including North American Blue Energy Partners, Aldyl Argentina, and Hainan Breey Energy.

Initially, the CPP was intended to circumvent sanctions, offering little to no transparency; some companies working under this framework do not even have a website. Standing contracts will transition to the new law keeping virtually all their terms. However, from now on, it is expected that there will be more publicly available information, at least as the U.S. is likely to demand it for new deals.

The Reform has brought the two frameworks closer together, although the CPP remains considerably more attractive to investment. The main concern is that, in practice, in both cases the investor must make all capital commitments, but in the joint venture, PDVSA is still holds a majority of shares.

U.S. licenses to control the flow of Venezuelan oil

The way in which the U.S. eases or lifts sanctions is the other vital piece to open the industry to foreign investment. So far, the Treasury Department’s OFAC has introduced a series of general licenses to authorise for exploration, production, and trading.

What has become clear is that the U.S. government wants to have control over the oil industry. The Treasury, State and Energy departments are tasked with supervising different activities, from the purchase of machinery, technology and services to extract oil, to the payment of taxes to the Venezuelan state, to the export of crude to third countries. Each of the licenses also explicitly rule out transacions with entities in Russia, Cuba, North Korea, and Iran; and in some cases, China.

The new relationship with Beijing is still unclear. Although there are measures to exclude the Asian giant, Trump has expressed his desire for it to also be able to not just buy, but also invest in Venezuelan oil. Here, a difference must be made between large, often state-owned Chinese corporations such as CNPC and SINOPEC; and smaller producers and “teapot refineries” and upstream investors that thrived by finding ways to bypass sanctions.

Eventually, what can be expected is that sanctions will be lifted overall, when a new government is duly recognised by Washington, DC, after elections that are deemed “free and fair.” This has been hinted by statements from Trump administration officials and acting President Delcy Rodríguez.

3. How fast can production increase?

Oil is 90% politics.

The key factor in Venezuela’s oil industry is and has always been politics, in many cases overriding otherwise determining economic considerations, like the price of the barrel. The bountiful oil fields have always been there, and oil continues to be a lucrative business opportunity. The country’s recent history shows this. Ups and downs were determined by liberalisations and state overreaching, especially as nationalisations were mismanaged, unlike in other petrostates like the Arab Gulf states or Norway. U.S. sanctions have also played a role in stifling the industry, or allowing for more breathing room through waivers.

The crux of the matter now is, therefore, to what extent will Caracas create the conditions for investment to flood in, at the same time that the Washington, DC eases sanctions? And beyond reforming laws and lifting sanctions, how are both capitals generating a sufficient level of trust and security?

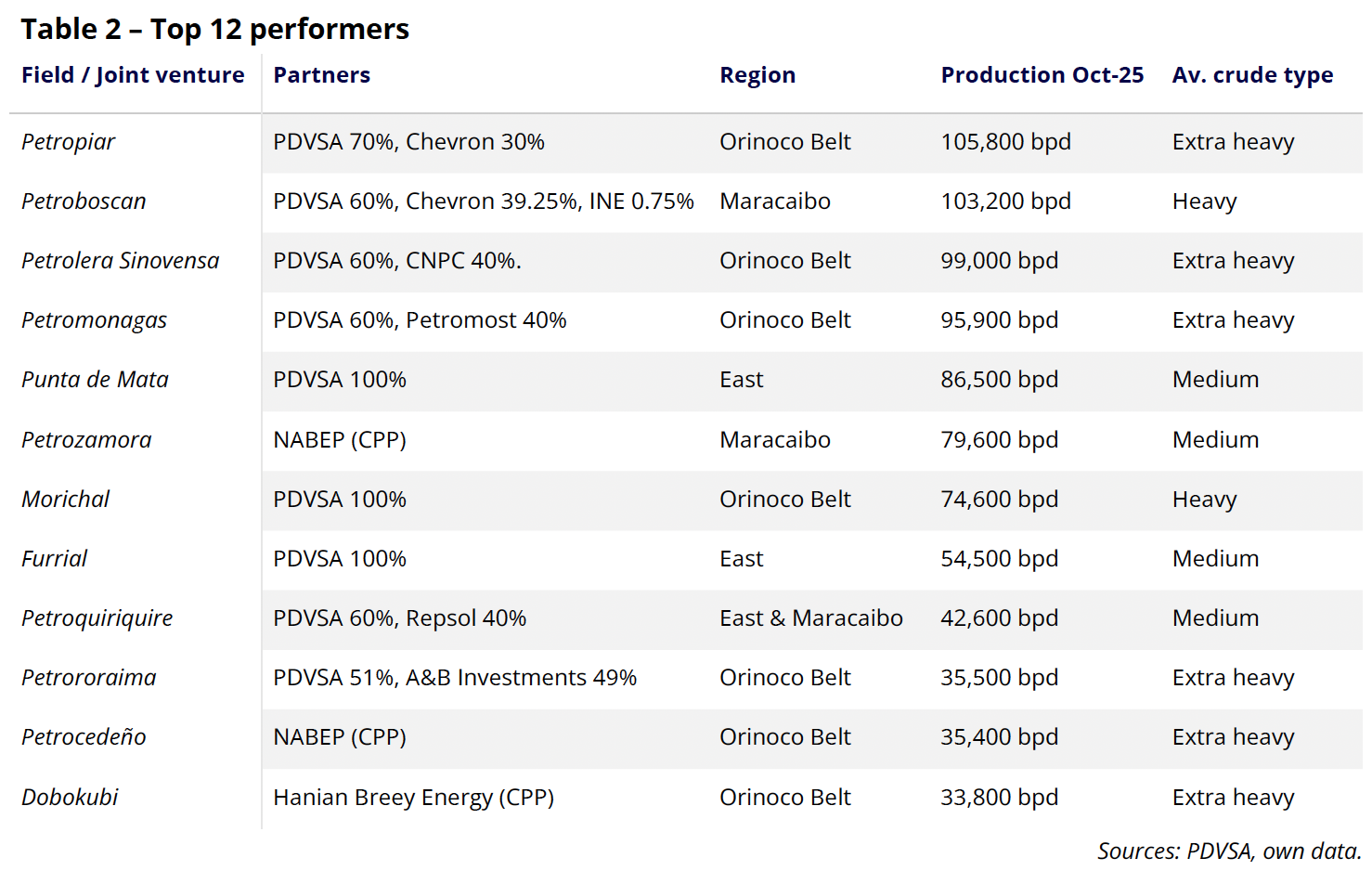

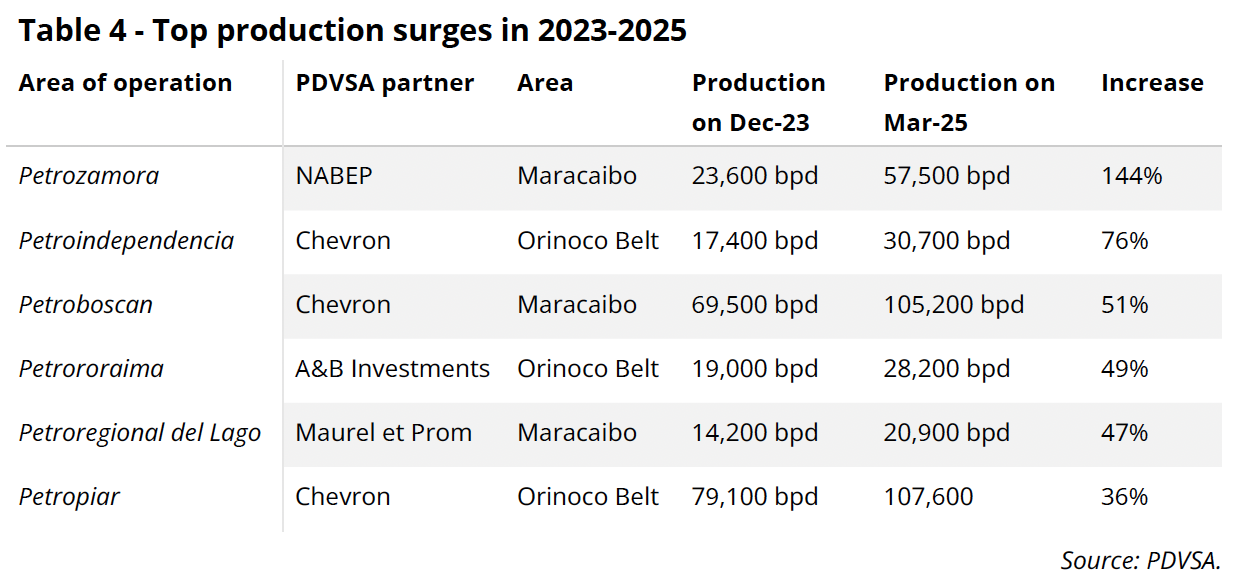

The latest Reform is building and expanding on two production frameworks that have been tried and tested: the CPP and the “Chevron Model,” alongside with sanctions waivers. In the past, these have unlocked fast growth in various oil fields, by offering investors greater control over operations as well as larger profits, resulting in greater efficiency. In a series of cases, energy companies have taken advantage of existing infrastructure and ample oil deposits to hike production in just a few months.

Considering a current production of 1,120,000 bpd, our base case estimate is that it will reach 1,340,000 bpd by December 2026, and 1,610,000 bpd by the end of 2027. The figure is not subtracting imported diluents from the final count, but rather calculating the gross output of crude oil barrels.

Table 4 shows a list of brownfield projects where output was revamped quickly even within a high-risk, restricted framework. The selected period starts with the introduction of U.S. Treasury licenses under the Biden administration and ends with their rollback during Trump’s second term. With reforms in Caracas and an easing of sanctions from Washington, DC, the contracts used here could be rolled out to the rest of the country, and now with more transparency. The added legal guarantees could also enable larger investments into greenfield projects, boosting production across the board.

The process will have its own bottlenecks and hurdles. Most large corporations will hold out while there remains a high level of risk and of uncertainty. The Ministry of Hydrocarbons also has the tedious task of reviewing dozens of joint ventures and CPPs with a limited technical capacity, before it starts to evaluate new investments; all with a bureaucracy that took months and years to process a small handful of requests. Moves to strengthen the capacity of the ministry and PDVSA, and to streamline procedures, will be crucial.

4. Orinoco Oil Belt: Development cost comparison with North American resource plays

Expert commentary by Roy Luck — Energy Geoscience Consultant and Principal, APEX Subsurface Consulting LLC.

Contact: roy.luck@apexsubsurface.com — www.apexsubsurface.com.

The largest oil resource plays[1] in the Western Hemisphere are the Alberta Oil Sands in Canada, the Faja Petrolífera del Orinoco (FPO) in Venezuela, and multiple unconventional (a.k.a. ‘shale’) formations in the United States – the largest of which is the Permian Basin of Texas and New Mexico (sub-divided into the Delaware and Midland basins to the west and east, respectively). The Alberta Oil Sands and the FPO are bitumen deposits in highly-porous, permeable sandstone, challenged by heavy, viscous oil. Over half of Alberta’s bitumen output comes from Enhanced Oil Recovery (EOR) projects involving steam or polymer injection to improve oil mobility and boost production. The remainder is recovered by strip mining, inapplicable to the FPO. By contrast, the Permian Basin ‘Wolfcamp’ reservoir has mobile, light oil, but is challenged by low permeability requiring hydraulic fracturing of horizontal wells to deliver economic production rates.

Comparing well economics across basins in different jurisdictions is challenging. This research note compares per-well Unit Technical Costs (UTC, defined as CAPEX per barrel of reserves) for each play. The per-well UTC approach does not take into consideration facilities CAPEX including upgraders and pipelines (FPO is under-developed away from existing projects), or OPEX considerations (bitumen production involves steam generation for Canadian thermal EOR projects, and blending with lighter oil to facilitate transport in Canada and the FPO). UTCs are far lower than ‘breakeven prices’, which reference the price/bbl required for NPVX=0 at discount rate X. Steep decline rates for unconventional wells necessitate higher well counts that impair full-life-cycle Internal-Rate-of-Return (IRR) and Net-Present-Value (NPV) metrics for unconventional development, relative to bitumen. This is offset by lower realised revenue for bitumen, and OPEX related to steam generation and diluent. Adding incremental production to existing projects and networks is less expensive than new projects that may require upgrading capacity in the case of the FPO.

In Alberta, the most common in-situ bitumen development strategy is Steam-Assisted Gravity Drainage (SAG-D), a thermal EOR technique that involves pairs of parallel steam injector and producer wells 1 km in length at ~1500’ depth. The average well pair costs $10MM for drilling and completion (D+C), and recovers 2 MMbbl for a UTC of $5/bbl per well pair. EOR is capital-intensive; for new projects, SAG-D facilities CAPEX accounts for 60% of total spend, implying a project UTC of $12.50/bbl. At YE 2025, EOR projects in Alberta and Saskatchewan contributed ~2 MMbbl/d.

In Venezuela’s Faja del Orinoco, the typical well is a 1 km lateral at 3000’ depth, with two forms of artificial lift – downhole diluent injection and progressive cavity pumps at surface. D+C costs are $6MM per well, with each well expected to recover 1.5 MMbbl, for a UTC of $4.00/bbl per well. Integrated projects include upgraders that increase export product value, but add substantial CAPEX. The sample size is small (5 projects), but CAPEX allocation to drilling has averaged ~30%, implying project UTC of $13/bbl. At YE 2025, the FPO contributed ~0.6 MMbbl/d; peak output was 1.2 MMbbl/d in 2015.

The Permian-Delaware Basin has the lowest breakeven costs in the unconventional realm ($40-$50/bbl); the average well is a 3 km lateral at 10,000’ depth. D+C costs are $9.5M for longer wells with fracture stimulation; the average well produces 0.6 MMbbl for a UTC of $16/bbl. Compared to bitumen production, a higher percentage of CAPEX is allocated to D+C in unconventional resource development (70-85%). At YE 2025, the Permian Basin contributed 5+ MMbbl/d.

A second metric compares resource density per unit area. This approach is best applied to the two bitumen resource plays. The Alberta Oil Sands cover 140k km2 with 1.7 Tbbl resource (average 12 MMbbl/km2); the FPO covers 55k km2 with 1.4 Tbbl resource (average 25 MMbbl/km2). The FPO has thicker pay and lower viscosity, but no mining potential. To date, investment in the Alberta Oil Sands exceeds $500B, ~20 times that of the FPO.

Historic well performance and cost data indicate that lateral wells in the FPO can be competitive with the North American resource plays on a UTC basis, assuming that commercial terms are formalised and the security climate improves. With major oilfield services firms expected to return to Venezuela in the near term, D+C costs should reduce, and operations scale and efficiency should improve. EOR implementation will further improve project economics in the FPO, where collective industry experience is limited to small-scale pilots. Multi-lateral wells are also an option. Refurbished upgraders and more reliable diluent supply provide additional upside.

[1] A resource play is a large contiguous area, covering the subsurface extent of an oil-bearing reservoir with limited geological heterogeneity, that has been de-risked by appraisal/development drilling. Resource plays are typically developed by multiple operators, using minor variants of a standard development scheme.